A little less than three years ago I stumbled out of the Peruvian Andes. I had just finished a walk of 13 days and nights around Inca ruins and frozen peaks. I grabbed a shower and some beers in Cuzco, and then high-tailed it to Central America. Four months I spent there wandering the jungles of Guatemala, Honduras and Costa Rica.

Since my return to God's Country in 2004 I have hardly ventured out anywhere. A few days here, a few days there---nothing extraordinary and nothing south of the Rio Grande. After spending 14 years walking alone through the wilds of Latin America, this unaccustomed rest and relaxation was odd.

And I have said since my return that if I did not get back to the jungle I would go mad.

That madness is near but its cure has arrived. This December 19 I leave for two weeks in the solitude of the Guatemalan jungles. Many are the Mayan ruins up that way, and many are those I have not yet seen.

All have heard of Tikal but there are many others---and all with weird names like Uaxactún, El Zotz, Nakum and Yaxhá. These places were once thriving city-states but now are populated only with reptiles, pumas and other such beastly inhabitants.

And of course there are monkeys. Lots of them. Too many of them. And I hate them all. From a distance and upwind one might think these simians cute. Up close and personal the creatures are filthy, smelly, worm-ridden, flea-encrusted and fecal. And they perform things in public best left unmentioned.

Occasionally some traveler makes his way beyond Tikal, but to go much further one needs all the usual backpacking stuff. And the going is tough indeed. Map, machete, a big knife, compass, all kinds of medicines and ten days of food and fuel---one needs them all to really get out into the forest.

And it needs to be said that the jungles of Guatemala resemble not at all the fantasies spun by Lion King-addled environmentalists. Such gullible and simple sorts claim all kinds of things for the rain forest. They believe it to be a kind of Eden.

The reality is that the jungle is a kind of Hell---hot, humid, filled with biting and disease carrying insects, crawling with venomous snakes and populated with animals that are dedicated to the proposition that all men are created to be devoured.

Sounds like my kind of place.

This map shows a little of where I will venture.

From the town of Flores one makes a route by truck to the village of Carmelita. From Carmelita there is a four-day walk to the great Mayan center of El Mirador, the largest site in Guatemala. There is a difficult connecting path between this ruin and Tikal. Or one could continue to Dos Lagunas, like El Mirador near the border with Mexico.

Between Tikal and Carmelita lies a path I followed some years ago. It connects the ruins of Uaxactún and El Zotz.

All of this jungle is seldom visited. To walk all of it will require a great deal from my 53 year old body.

But it will require more from the mental and spiritual side. Walkabouts such as I have planned for Guatemala are always like this. The body expends every possible effort to the limits of physical endurance. At the moment of collapse the spirit and mind take over.

It is only then that you can really enjoy and understand what you are doing and why. There is a sort of peace then, a welcome euphoria---odd things to feel in such an inhospitable land.

The Lost White City of the Maya has long been rumored to lie somewhere between the headwaters of the Paulaya and Platano Rivers in the jungles of the Mosquito Coast in Honduras. During my second attempt to find it (1989) I was stuck for a time in the Caribbean town of Trujillo.

In those days I was broke, and so always sought out the cheapest accommodation possible. This meant the Hotel Central. It was a terribly ramshackle affair, chock full of bugs and myriad crawling things. Of course there were neither lights nor running water.

During the night I had to search for the toilet. The thing was in the basement. I noticed something strange when I found it. The water in the bowl was filled with ancient urine and moldering feces. There was no method to flush the thing other than fill up a plastic bucket with river water and pour it into the bowl. This chore had been long neglected.

I accepted the inevitable. Putting the flashlight between my teeth I began to loosen my pants. Then that I noticed that the goo in the bowl was moving. It looked like a pot of boiling stew. A closer look showed a huge brown rat stuck in the bowl. It tried to extricate itself from the mess it was in, but the slime inside the toilet did not allow the wretched beast to get a decent grip. And so every attempt to escape ended with the animal sliding back into the grime.

Had I squatted over the toilet before noticing that rat, the thing would have been able to use a dangling part of my God-given anatomy as a life-line to freedom.

Every male who has read what I just wrote most assuredly shuddered. And with fair reason. But now I present to you a tale so shocking, so terrifying, so damned grotesque that children will be sent fleeing in horror upon hearing it. Men will become pale with fear. Women will clutch their men and girls in a vice-grip of protection.

Ladies and gentlemen, I present to you the candirú (Vandellia cirrhosa).

It is a type of catfish that was certainly designed in Hell. The candirú is found in the Amazon and its tributaries. It is small, perhaps an inch in length and pencil-thin. It has an odd habit of swimming into the human anus and genitals. It is attracted to urine and blood, and has been known to swim up a urine stream and enter the urethra. When there it erects spines to hold it in place and begins to feed on blood and tissue.

The pain of such an attack is simply beyond words. Men have been known to cut off their penises after a candirú infects them. There is no cure except for surgery or the following:

A traditional cure involves the use of two plants, the Xagua plant...and the Buitach apple which are inserted...into the affected area. These two plants together will kill and then dissolve the fish. More often, infection causes shock and death in the victim before the candirú can be removed.

For good reason the candirú is more feared than the vastly over-rated piranha.

Here is a first-hand account of a candirú attack. It is not for the faint of heart. Some amusing excerpts:

The fish penetrated the victim's urethra while he was standing in the river urinating, actually emerging from the water and entering his penis…He reported trying to grab hold of the fish, but it was very slippery, and it forced its way inside with alarming speed. The candirú's forward progress was blocked by the sphincter separating the penile urethra from the bulbar urethra. With the passage blocked, the fish had made a lateral turn and bitten through the tissue into the corpus spongiosum, creating an opening into the scrotum.

So the next time you have a desire to seek out ancient Honduran toilets or to venture into the Amazon basin do take care. You have been warned.

To a normal person it might seem like I have spent a good portion of my adult life engaged in trying to end it. That was not my intent, of course. Most of my time since college has been spent living in or working in or backpacking in Latin America. When I was not doing these things I was thinking about doing these things.

Eight years ago I was taking a bunch of high school students for a 4-day hike through the Argentine Andes. There was a high mountain trail of sorts that traversed several ridges. It connected a series of huts and lakes that were scattered throughout the area. I had been to about all of them. You can get a taste of the place here.

On our third day out we were climbing a scree slope to a ridge that overlooked our final campsite, the ranger hut at Laguna Jakob. I was walking about 30 feet behind a student. Her foot loosened some small rocks, which then allowed a slab of slate the size of a card table to cascade down the slope. I saw it coming toward me but had no time to get out of the way. It crashed into my leg right above the kneecap. Had it hit that bone I would have been crippled for life, and my backpacking days would have been over.

I yelped in pain, but still managed to make it to the ridge only a minute away. The pain seemed manageable. Unknown to me that rock had crushed tissue, nerves and blood vessels. The wound left only a small exterior mark, but under the skin the damage was extensive. Blood spilled out into the surrounding tissue and began to press beneath the skin, and slowly ballooned my leg into a nightmarish shape.

The hut was one hour away straight down. Most of the students began to descend as I followed behind. After ten minutes it was clear that I could not go on. The pain in the leg had immobilized me. To put any pressure on it at all was to feel something like an electric jolt course through my body. It was the most intense physical pain I had ever experienced. I had a walkie-talkie and used it to call the students already at the refugio. A group headed back up the mountain and brought me down with a stretcher. A 9th grader brought with him some medicines from the rangers to kill the pain, 3 bottles of Argentine beer. He was a good kid.

At the ranger hut I had these photos taken of my knee. Pretty, yes?

The next day I arranged for a horse to carry me off the mountain and into the town of Bariloche. A doctor in town told me that the bruise on my leg was the largest he had ever seen. Well, yes.

One week later in Buenos Aires the knee was still swollen. I went to a doctor who took one look at it and told me that he would have to slice it open. He did not bother with any anesthesia since there was no sensation in the ruined tissue. As soon as the scalpel cut into the flesh a bunch of semi-coagulated blood poured out of it. It had the consistency of coffee grounds. The doctor was surprised at the quantity of the blood. He squeezed the skin and more and more blood came out. When he was done there was a full quart of gooey blood soaking up several towels. The skin around my knee resembled a deflated basketball. He wrapped it up and I headed home.

Three days later while showering I accidentally rubbed the scab covering the scalpel cut. More blood gushed out into the bath tub. It did not stop until the shower curtain and both my legs were covered with blood. All that scene needed was the screeching violins from Psycho.

To this day I have little sensation in that knee. The flesh beneath the skin there feels weird and bumpy. It is now impossible to conjure up the pain, which is a good thing. I do remember that 9th grader and the beers, though. He was a good kid.

Luckless Iguanas and Monkeys of Gold

Like Napoleon's army, a solo backpacker travels on his own stomach. I have walked here, there and everywhere, usually alone and always hungry. I can pack ten days worth of food without much strain. But such fare is monotonous: Ramen noodles, oatmeal, dried soups and pasta, macaroni and cheese (the cheap Kraft kind) and coffee. Such haute-cuisine is chosen for its weight, not for its taste. No cans are permissible: too heavy, too bulky. Also excluded (for me anyway) are those delightful backpacking meals offered in myriad flavors and recipes. They cost too much, are unavailable in the jungle and Andean haunts I love and are a bit, well, dainty.

A true backpacker eats to walk not walks to eat. I leave the good eating for the end of the hike after I have earned such pleasure through the most excellent method of having endured physical pain. And that---among many other things---is what solo backpacking is: accepting day after day self-inflicted, brutal physical pain all in the service of beauty and solitude. And as God is my Witness and my Judge it is always and everywhere worth it.

There are times when I walked out of mountains and jungles that I felt myself invincible simply for having thrived alone for days on end in a hostile place---places such as Choquequirao and El Petén. Accomplishing such vastly increases the delight in real food, what one would find in a Chinese restaurant in Cuzco or in a chicken joint near the ruins of Tikal.

There could be food available during a hike. It is so in the Peruvian Andes. Setting up a tent near a hut or a village will lead to offers of rice, beans, plantains and yucca. I reciprocate with my own cooking. Those Ramen noodles which bore me excite the locals. Both they and I are better off.

Occasionally there is food available in jungles as well. It was so during one of my many Honduran walks. Some years ago I was looking for a gold mine. Or a lost city. Or both. Anyway, I was somewhere in the province of Colon walking from the Sico River toward the Mosquito Coast.

The trail was muddy and difficult. I ended up in a village along some unnamed jungle river. The locals were hospitable and curious, and they competed among themselves to see who would provide me with a place to camp. The winner was the Jones family. I set my tent in front of their hut. The Jones clan had migrated to Honduras almost 100 years before, first from England, then Jamaica, then the Bay Islands. They settled in the jungles of the province of Olancho on the Honduran mainland. There they contracted the 'gold disease,' la fiebre de oro. Over the ensuing decades the life and vitality of this family was drained away by the fruitless search for gold. When I met them they had so intermingled with the locals that they had forgotten much about their heritage; they had become pure Honduran.

My first night there the Jones family invited me into the hut for a dinner of rice, beans and iguana. The unlucky reptile was pulled alive from a cotton sack and slaughtered then and there. It screamed and writhed while the knife sliced it open but at last gave up the ghost. I had never eaten iguana and hoped never to eat it again. Its flesh was oily and repellent, and nothing like chicken.

The Jones family talked of gold, of nuggets seen and unseen, of rivers somewhere deep in the jungle that shimmered from the glint of golden ore that lay beneath the surface waters. They fed me hints of a strange god, a monkey god of white gold buried by the Chorotega Indians when they heard of the approach of the conqueror of the Aztecs, Cortez. The Jones swore to me that they could find that monkey god. They wanted me to go with them. We would get some rifles ("for the crocodiles") and some canoes and head out on the river in a search for white gold. Though their eyes had the look of madness, I said I would think about it. It turned out that I declined the expedition, to my occasional regret. I know perfectly well what happens when a group of well-armed gold seekers finds gold. Men die.

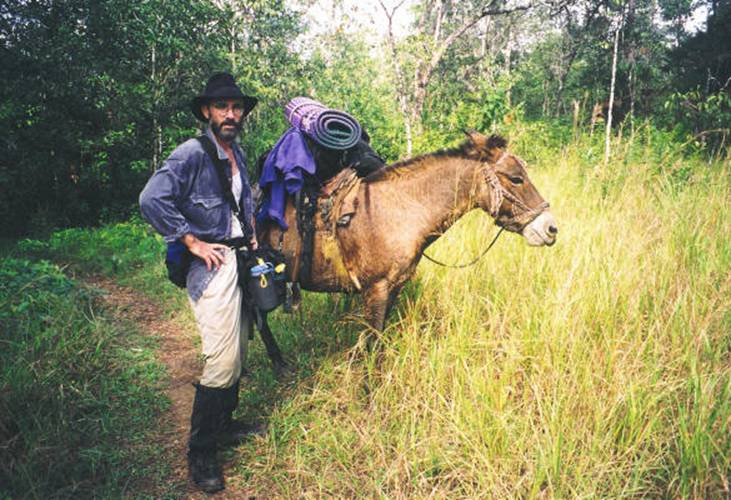

After a few days I walked further into the jungle to find another member of the Jones clan, the patriarch really. He had a house some 20 miles away. It took some doing to get there. There was no path but only a muddy trail used by horses and mules. There was no way I could find the house by myself, so I hired a mule and driver who knew the route. The driver attached a sack to my mule which contained a live iguana. This was to be my dinner, alas.

Mule driver with dinner

It took some time getting there as I knew nothing of the ways of mules. The beast ended up throwing me off into the mud near a river. I responded by punching it hard right below its eye. I walked the rest of the way.

The patriarch's house was remarkable. It lay along a stream that he had dammed to supply power to the machines that sluiced for gold. He also had built a crude canal system. There were several houses; the patriarch Jones and his wife put me up in their own. After the ghastly dinner I asked them about the tale of the monkey god. For the next hour Jones spoke of treasure, of conquistadors infected with gold fever, of Indians hiding their precious god from rapacious Spaniards, of doomed expeditions lost while seeking the monkey god of gold.

When he was done Jones saw the crucifix around my neck. He asked to touch it, and then held it between his thumb and forefinger in the same way that I hold the Rosary. His eyes sparkled as he exclaimed, "It is gold!" The others in the house gathered around to touch the crucifix. They were not entranced by what it represented but by the golden ore of which it was made.

I left the next day. The driver came with me. We both walked as that damned mule had stayed at the house. Back again at the first Jones' house I set my tent and marveled at lives wasted away in forsaken jungles in the quest for shiny metal.

Yet there is something to it after all. The tale of the monkey god has never ventured far from my thoughts. Dream-like and ghostly, it wanders in and out of my consciousness, as tempting and as alluring as a fantasy of a beautiful woman.

|

Camping at the Jones house |

|

The Jones Family |

|

River near campsite |

|

Me and the damned mule |

There are four ways to journey to foreign lands. In order of difficulty and risk they are: tourism, travel, adventure and exploration. I have done all of them.

Tourism is what most people mean by 'travel.' All hotels, transportation, food, photo opportunities, sites---everything, in fact---is arranged beforehand by an agency that specializes in such things. There are no surprises, for those who pay good money for such a tour do not want any. These are people who have no time to do research, learn the rudiments of a foreign language, and to make their own flight arrangements. Tourism is easy, popular and can be entertaining though at times it can be boring. Remember, no surprises! All hotels are clean and have hot water and one seldom gets ill eating the food.

The next step in difficulty is travel. One makes his own arrangements and attempts to learn street and restaurant survival techniques in a foreign tongue. This takes some time as often the traveler does not really know exactly where he is going or where he will stay when he gets there. College students making their first foray to Europe, graduate students following the 'Gringo Trail' from Mexico to Peru and retired folks who have time and an adventurous spirit become experts in travel. It is seldom boring, but it can be---and many times it is---trying. Cold water pensions or hostels and street food are well known to the traveler, as is the occasional bout with dysentery.

There are some hybrids that combine tourism and travel. They usually have the words 'adventure' or 'eco-' (as in 'ecology') in them. Thus something called 'adventure travel' and 'eco-tourism.' But do not be fooled, both are really types of tourism. All is arranged, planned and organized. The customer is just along for the ride. These trips can certainly be fun, but there is nothing heroic or difficult about them.

Adventure requires a desire to really get off the well-traveled track, to go the weird places---like obscure Mayan ruins buried deep in some God-forsaken jungle. It is also expensive, as the adventurer must have tent, stove and all the rest of the backpacking kit. He---and occasionally she---must be prepared for the unexpected (what I call the 'X' factor) for the unexpected is part of the reason for planning an adventure in the first place. And trust me, the X factor always happens. Adventurers plan on getting sick, sleeping in odd places, being dirty for days on end, becoming unfamiliar with toilets, having close encounters with animals and very strange people, and eating unrecognizable fare---that is why it is called 'adventure.' Adventure types can be seen hiking frozen islands, soloing mountain peaks and reveling in avoiding death when it appears.

Exploration---going where few have gone---is getting tough to come by these days. Most areas of the world have been mapped and McDonaled. Even Everest, which 50 years ago was seen as the peak event in the exploration of the age, now is almost tourism. No kidding, about anyone can pay an agency upwards of $65,000 to take them to the summit of Everest and even back down again---no mean feat, as 14 people died there a few years back. Poles are well-traversed---there are tours there---Africa has given up her secret of the source of the Nile, Asia is way over crowded. The only real remaining place to experience exploration is South and Central America, but even there it is quickly succumbing to tourism. This is not a complaint, just an observation.

One rule of thumb: if a bus pulls up to your camp site and unloads 50 Japanese tourists with matching suits and cameras, it is time to get out of there. When I was first in Tikal 20 years ago I was about alone in the jungle there. There was only a place to camp, one place to eat and no hotels. Now it is as crowded as Disney World. What all this means is that the adventurers and explorers must go further and further 'out there'. Rather than Tikal one must walk to Nakum. Rather than the Inca Trail one must walk across the Andes to Choquequirao. And so on. But even those places will be well traveled one day, forcing the explorers and adventurers way back into the hills and trackless jungle.

The last remaining areas for exploration in Central America are the far reaches of northern Guatemala, the Mosquito region of Nicaragua, and Honduras, specifically the region between the Paulaya and Platano Rivers. Tales of monkey gods and lost cities abound. And that, dear reader, is why I am going there. After which...what? How will I be able to beat that, assuming I survive? The very thought disturbs. Maybe then it will be time to retire all my backpacking gear. After all, I will have seen all that is worth seeing in Latin America, as far as I am considered.

Or I could climb Aconcagua. Or spend time traversing the Venezuelan jungles. Or venture forth into the grasslands of Suriname. Or cut across country from Perrito Moreno National Park in Argentina all the way to Chile.

Ah...I feel better already!

I once lived in Argentina. It was the perfect place and I taught at the perfect school—just as today I live in the perfect place and teach at the perfect school.

One reason I thrived in Argentina was that I had the time to walk around every single nation in Central and South America except for two of the Guyanas. Most of every vacation I spent in a tent in some jungle or upon some Andean ridge.

Nice work if you can get it. And I got it.

Here is one such Andean ridge, near the Argentine town of Bariloche. It is about three days walking to get there. The small lake is called Laguna Negra. The trail to the town is near the exit stream. I camped there a night or two, and then headed up those walls and walked another three days into the Andes toward a village where there was cold beer to be had.

I stopped for a moment after traversing the rocks and took this next photo. The lake in the distance is part of a system of lakes, the largest of which is Nahuel Huapi. All their waters eventually end in the Atlantic Ocean.

From those lakes I journeyed further south into Argentine and Chilean Patagonia. It was not my first time there nor my last. I wanted to see Glacier National Park in Argentina. There one could walk to the base of Cerro Torre, a most spectacular mountain. The route to the top was once considered to be the hardest climb in the world. It was accomplished only in 1974 but not before claiming the lives of many.

I am standing about three hours from the base of Cerro Torre. To my right there is a small crystalline lake fed from the glacial runoff. To my left is a massif that goes up and up until ending in a wall of blue ice.

If I look cold it is because I am cold.

Here is the mountain on a clear day, a rare thing in those parts. This photo is from the web.

I stayed near Cerro Torre for a few days and then headed into Chilean Tierra del Fuego and the island of Navarino. This odd little place boasts the southernmost permanently inhabited town, a naval base called Puerto Williams. The landscape on Navarino is other-worldly, all ragged peaks and tundra.

The island is infested with beavers. These beasts have almost denuded the center plateau of trees, making the middle of Navarino full of small lakes and beaver damns. Chilean officialdom hates the beavers and pays anyone a small sum to kill them.

The walking on Navarino is superb. One leaves the naval base and begins a four hour ascent up a forested incline to the plateau which comprises most of Navarino. All is windy and cold up there. Here is the western end of the island.

Those times in my life—perhaps 14 years all told—I spent exploring ‘wild weird climes lying most sublime, out of space, out of time’ are not yet over, but I have placed them aside for now. Other things call me and other responsibilities claim me.

But the hold Central and South America have on me has not at all lessened. To this day, on this very morning, I imagine going back for a spell, not to live or work—been there, done that—but simply to travel. There are still some jungles and mountains down south that have not yet felt the tread of my boots. This situation cries out for a remedy.

I Hate Monkeys and They Hate Me

A friend said that if he were in the deepest dungeon on earth with only the Bible as a companion, he would know what was going on in the world.

Nothing could be more true.

My friend and I returned from the lakes, jungles and byways of Guatemala to find a world still enmeshed in wars and rumors of wars, trivial politics, assassinations, Clintonian embarrassments and all around murder, mayhem and tomfoolery.

Truly, there is nothing new under the sun.

I give thanks that some things never change. And one thing that will never change until Christ returns is the hatred I have for monkeys and the hatred they have for me.

Our mutual animosity began in Costa Rica 20 years ago when I struck a white-faced monkey square on his simian skull with a well placed rock. I did it solely for amusement. He replied by getting his monkey pals to chase me through the jungle and throw feces at me.

Bastards.

The word spread. Now whenever I encounter these demons they continue their jihad against me. We have made war all through Central and South America. This war continues apace.

One week ago while on a lonely jungle trail near the ruins of Tikal a fat bellied primate saw us ambling along. Ignoring my friend the monkey grabbed a substantial tree limb and threw it at my head. Had it struck home I would have been seriously wounded. My machete could in no way reach the beast, and as there were no handy stones about I could do nothing but spit out my hatred with shaking fist.

Our antagonist merely laughed as he and others began to pelt us with everything available to them. We retreated.

Bastards.

But never again. I say, never again. For this very day and this very hour I have ordered a piece of equipment that will put ‘paid’ to this war. Here it is.

It is the Double Eagle Pro Wrist-Rocket, accurate to 250 yards. Next year when I am alone in the jungles of Guatemala I will ensure that the first monkey I see has a bad day. A very bad day.

Depend upon it. Let us call it ‘victory through superior firepower.’

And please! Can we not have any of that environmentalist, animal rights and ‘jungle animals are cute’ nonsense? Monkeys are filthy, thieving, murderous, verminous, worm-filled and eaters of their own feces. The only folks who adore them are folks who do not have to live near them.

People who live in jungles hunt them for sport and food. The Choco Indians of Panama believe that every white-faced monkey they kill will serve them as a slave in the afterlife. I know that every one I kill will be sent straight to Hell to serve as a servant of Satan.

Works for me.

Traveling at random on the web can have side-effects. I do not mean carpal tunnel or bug-eyes, but occasional bouts of nostalgia and melancholy. These are not necessarily bad things, but reminders of times long ago and far away. They sneak up and surprise, and for a moment they control your heart and mind.

It was twelve years ago. I was married then and teaching in Argentina. My wife Marlene and I and another married couple from the school, David and Stephanie, decided to take a lengthy backpacking trip through the Argentine Andes. It almost cost our lives. It should have cost our lives.

We headed out from Bariloche, an Argentine town nestled in the Andes and about the finest place on earth. We planned on walking to a series of lakes, camping at each one and then heading out to another the next day. The trip should have taken five days. It took nine.

Our first campsite was pleasant. It was around a glacial lake filled with chunks of ice. In the morning we spent a long time making our way around the lake. We had to climb a bit to the sloping rock face that went around it, as there was a great deal of snow and ice near the lake edge. A careless step there and one would have plunged backpack and all into freezing water.

The next day we crossed a pass and dropped into a valley. At the bottom we started our climb to the next lake. It began to rain. By the time we reached the lake we were soaked. Our gear was dry though, and so we set camp and went to sleep. The rains increased, and while we slept an Andean storm blew in. Our tent held up but the other did not. It collapsed during the night, and a cold and wet David and Stephanie came into our tent for the rest of the night. It was cozy.

Daylight saw less rain and even a bit of sun. David dried out his tent and gear, and we elected to stay there another day. On the fourth morning we broke camp to a sunny sky. Full of good cheer, we headed up another pass and walked down a wide valley. We stopped an hour or so on our way down to get our bearings. It was clear that the next lake was beyond a pass that we could see from our vantage point. It was covered in snow and ice, and could not be crossed.

We were a little perplexed about what to do. Turn back? No, we did not want to face failure. We could see quite a ways down the valley, where a small stream emerged from a rock face right behind us and flowed down. We knew that somewhere in that direction was another connecting trail to the lakes we wanted to see. So we decided to simply continue down and eventually find the trail and head up it.

The next two days we walked down into the valley, which gradually narrowed. On either side were steep and shockingly beautiful cliffs of ice and granite. Soon we had to walk part way in the stream as the ground near its banks became too difficult to traverse. We were still having a grand old time. We camped at a small flat spot. That night the rains came.

David and Stephanie’s tent again collapsed, and the four of us stayed dry in mine. The morning went without breakfast or—far worse—coffee, as it was too wet to break out the stove. We just packed up and continued walking into the valley that had now become a steep canyon. We stayed as dry as we could but the rain soon overwhelmed our jackets. We walked cold and wet further down, down and down.

What had been a reasonable cover of trees now became a tightly woven forest of bamboo. It was impossible to move well among those damn plants. We had to look carefully, push some bamboo out of the way and take a step. Progress was measured in feet per hours. And still it rained.

After a day of this we made a miserable camp and went into the tent without dinner. The next day was the same, full of grays and water and cold. We could not go back even if we had wanted to, as the way up was now slippery and treacherous with mud. There was only down and down. And so we went.

That day was like the one before, though the stream was becoming more of a torrent as the canyon walls grew closer to it. We plodded through the bamboo at an achingly slow pace soaked with rain and shivering with cold. All of us were in the first stages of hypothermia, though we of course did not know this. The shaking of our bodies and the noise it made from our clattering teeth almost made us laugh. We made our way for ten hours with no sight of any trail leading up and away from that valley.

We made a ridiculous camp among the bamboo, and all of us were in my tent. There was no sleep to be had but at least our bodies could be dry inside it. The next day the rains increased, the bamboo thickened and the stream became impossible to walk in. For it was no longer a stream but a roaring river that cascaded among boulders and it rushed toward the sea 300 miles away. Only now did we realize that we were fools who had made a series of bad decisions, each one magnifying the errors of the one before.

Our situation was beyond absurd—that condition had been in place days before. We were beginning to lose the ability to think clearly as our bodies advanced further into hypothermia. Our conversation—such as it was—was as if among a group of stammerers. Consonants were extremely hard to pronounce, especially the letter ‘c’. My wife and Stephanie both turned to me more than once and asked if we were going to die. I told them no.

Finally we advanced down that valley until we could advance no more. We had come to a ferocious river emerging from our right that dropped into a large pool of freezing water fifty feet below. The smaller river we had been following merged with it. There was no going forward, no going backward, no going left or right. It was the end.

We thought of where that bigger river had begun, and understood that the bank on the other side might be traversable—if we could get to it. We waded upstream in that frozen current, clasping each other’s arms to prevent being swept away. There was a shallow point, and David stood there a moment before oddly leaping onto an impossibly slippery rock. He stood as though drunk and leapt again, this time landing on the bamboo-encrusted bank on the other side. The three of us simply watched him as we stood still like idiots in the icy river.

He clambered up the side and disappeared. Seconds later he yelled out, “I have found the trail! The trail!” He was right. The trail that connected the lakes followed the river on our right. It began on the other side of that pass we could not cross because of ice and snow. Now David was on it.

The rest of us made it across and found David on the trail, on his knees. He was laughing. We joined him.

It was seven hours back to a ranger’s cabin. My body, so long in a state of adrenaline shock, now returned to a near normal condition. Pain entered and convulsed me. I discovered that every bone and tendon and fiber ached and throbbed. My boots, unknown to me, were soaked inside with dry and wet blood. My toes and feet were a shambles. It took six months to recover fully.

We heard later that four other hikers made the same decision we had made, though a few days before us. They did not make it. Just bad luck I guess.

Here we are before the hike, looking toward our upcoming adventure. We had no idea.

Update: Exactly one year later I returned to the Andes. I wanted—I needed—to walk the original route we had intended. No man enjoys living with defeat. He will make every effort to erase it. I erased it.

I headed out alone, but in the reverse direction the four of us had done the year before. It took five days to travel between the lakes. On the spot where we made our near fatal decision to continue, I exulted.

Here is the picture of me doing exactly that. Behind me to your left is the first lake where we camped when the rains began. The trail heads out to the left over the ridges and goes into the valley where we had almost come to grief.

Here is the full-sized pic. If I appear elated it is because I am elated. Vini, vidi, vici.

As a boy I spent much time wandering in dreams. The land of fantasy seemed a whole lot more entertaining than the chaotic land outside my mind. There was more to do there too—all sorts of jungles to explore and mountains to climb and ancient civilizations to uncover.

Such desires never left me. I never wanted them to leave me. Even as a man of 54 my mind goes to faraway places, to ‘wild, weird climes lying most sublime, out of space, out of time.’

At an age when most men were living lives of responsibility, parenthood and mortgages, I was meandering here and there somewhere south of the Rio Grande. For twelve years of that time I was actually employed in foreign lands, teaching adolescents about life and history while planning another foray into some God-forsaken jungle. And take it from me, all jungles are God-forsaken.

Twice during those years I was free from even the moderate task of holding a job. I wrapped up whatever loose ends needed to be wrapped up, and headed away for two years of solo exploring the lands beyond my own. When I tell this to normal men, the usual response is something like, “Damn, I always wanted to do something like that! I will too, one day.”

One day.

Such years passed in frivolity naturally had a price. I paid it. I continue to pay it, with interest, like a huge credit card debt. This is a report, not a complaint.

I today live safely and responsibly very much in normal time and normal space—and Oklahoma time and space are as normal as you can find. I am as comfortable as I ever have been, though I doubt this is a good thing. Men were not made to be comfortable.

I am reminded of this fact from time to time. It is not a pleasant thing to be reminded. Here was one reminder.

The remnants of at least ten pyramids have been discovered on the coast of Peru, marking what could be a vast ceremonial site of an ancient, little-known culture, archaeologists say.

These sorts of discoveries pop up from time to time, usually in some place in South America. When they do I curse the annoying and unaccustomed normalcy of my life. I always believe that I should have been the one to find that lost civilization. Many times in my travels in Peru I have passed by that site, never knowing what was buried there beneath the desert.

Not that I have never tried to find something lost. Some 20 years ago while in Guatemala I heard rumors of an incredible city lost in the jungles of Honduras. It had a name—‘The White City of the Maya’—and even showed up on the Texaco map of Honduras. True, Texaco had merely guessed at its location, and placed it between the Platano and Paulaya Rivers.

The stories of this ‘White City’—La Ciudad Blanca—intrigued me then. They intrigue me now.

The legend of the fabulous lost city of Honduras was first recorded by Hernan Cortes…Cortes’ search for this Central American El Dorado marks the beginning of the Ciudad Blanca legend, as well as the first of many failed attempts to find this lost city.

Nearly twenty years later, in the year 1544, Bishop Cristobol de Pedraza, the Bishop of Honduras, wrote a letter to the King of Spain describing an arduous trip to the edge of the Mosquito Coast jungles. In fantastic language, he tells of looking east from a mountaintop into unexplored territory, where he saw a large city in one of the river valleys that cut through the Mosquito Coast. His guides, he wrote, assured him that the nobles there ate from plates of gold.

Of course that story pulled me out of Guatemala and into the Honduran jungles. There was the near shipwreck, the worms embedded in feet, the vampire bats; there was the journey to the gold mines and the rough men met along the way, the tales told there of an ancient and golden monkey god, the jungles that could easily swallow a man—or a city—whole.

I never found that city, but that did not matter—much.

All tales of lost cities in Latin America have in common stories told by Indians to gullible Spaniards, legends of gold and of great temples of stone, of attempts to find the place that always end in death and betrayal, of horrors of human sacrifice and ancient tombs. In short, such things contain every possible element to entice an adolescent mind to fantastic dreams of exploration and conquest.

Most have heard of El Dorado, and even a few have heard of Paititi. The description of Paititi fits every dream category.

Paititi refers to the legendary lost city said to lie east of the Andes, hidden somewhere within the remote rain forests of southeast Peru, northern Bolivia, and southwest Brazil…In 2001 the Italian archaeologist Mario Polia discovered the report of the missionary Andrea Lopez in the archives of the Jesuits in Rome. In the document, which originates from the time around 1600, Lopez describes a large city rich in gold, silver and jewels, located in the middle of the tropical jungle near a waterfall and called Paititi by the natives. Lopez informed the Pope about its discovery. Conspiracy theories maintain that the exact location of Paititi has been kept secret by the Vatican.

How is that for a conspiracy theory?

Many lives have been spent in the search for such things. Gene Savoy was one who did so. You have never heard of him, but many think he was the inspiration for Indiana Jones. He discovered more than 40 ‘lost cities’ in the Peruvian jungles, arguably making him the greatest explorer of all time. True, he was very much an oddball. But perhaps what he did could not have been done by a normal man.

But then, no explorer was a normal man—not Burton, not Stanley, not Speke, none of them. Normal men do not attempt such things, and for good reason. For the usual end of exploration is a lonely death far away from home. Those very few who succeed in their quest for the Grail become famous. The great many more who fail have bones moldering in the anonymous silence of distant jungles.

Those dream-tales that enabled me to survive my boyhood still enthrall, still enliven, still beckon. I am perhaps getting too old to answer now, although Savoy made his final journey in his late 70s.

By my calculations I have some time left. The race is on.

Somewhere south lies that Lost White City. A bit further on lies a monkey god of gold.

Update: Here is a 1985 photo of explorer Gene Savoy heading out to the Pervian Andes.

Here is a 1997 photo of me heading out into the Honduran Mosquito Coast looking for gold mines.

Weird.

I have walked in Central and South American jungles for twenty five years. At first such a thing was a mere lark but then became a bit of an obsession. My first serious foray about scared the Hell out of me. Perhaps it would have been better if it had literally done that.

I learned rather abruptly that to spend any time alone in the tropical forest I had to become acquainted with the evils associated with the place. And evils there be aplenty. You can simply discard the childish nonsense you learned in school and from the media about how jungles are innocent Arcadias full of friendly lion kings and monkeys, that they are a veritable cornucopia of miracle cures, and that they are inhabited by deeply spiritual natives who are one with the environment.

All this is gibberish. The jungle is full of death. It walks on four legs. It slithers upon the ground. It flies through the air. It wriggles in the grass. It lives invisible in a host of insects only to burst forth in the most hideous diseases known to man. It burrows into your flesh and organs. It infects and paralyzes and blinds. In the city you might be doctor this or professor that or senator so and so, but in the jungle you are nothing but prey.

Once this is understood only then can the magnificent beauty of the place be understood. And that is the secret. Real beauty is always dangerous—whether the beauty of a woman or a mountain or the open sea or the jungle. If you desire such things I salute you and wish you well. If you manage to capture them you will at once understand what I mean.

If you desire an up close and personal encounter with the jungle you would do well to study the thing for a bit. It is cool to venture into the tropical forest but it is better to return from it. Learn what is really out there and learn how to deal with it.

Here is what is out there.

Malaria is out there. It is carried by mosquitoes but is itself a protozoa—what normal folk call a worm. Cover all exposed flesh twice a day with 100 percent DEET. Soak your hat and clothes with it. Take anti-malaria prophylaxis. Oddly, malaria kills people in the US. It takes some time after the bite to get sick, so that New York guy who vacations in Bali for two weeks gets sick a month after his return. The doctor naturally has never seen malaria, fails to diagnose it and the guy dies. Just bad luck.

Leishmaniasis is another protozoa though carried by a sand fly. It causes sores that are very difficult to heal. And guess what? Flies are not deterred by DEET. Cover up your flesh and good luck.

Onchocersiasis is yet another protozoa carried by yet another fly. This pleasant illness blinds you and ruins the fat under your dermis.

Don’t drink the water. No kidding. For there be amoebas and much else. Dysentery is one result but typhoid and cholera are others. And you of course know that jungle animals urinate and defecate in water, yes? Forget those little water purifiers you see at REI. They are for grandmother’s backyard and will not survive even one use of the highly silted water common to jungles. Use iodine. You do not like the aftertaste? Tough. Would you prefer the flavor of animal urine?

Rabies is fatal; to die from it is unpleasant in the extreme. If you are bitten by a mammal in the jungle get the Hell out of there and to a hospital back to whatever passes for civilization down south of the Rio Grande. This is a good idea whether you have been vaccinated for it or not. Do not panic as it takes some time after the bite to develop symptoms. Bats are as common as fleas in the jungle, and they carry rabies.

Chagas’ Disease—American trypanosomiasis—is another protozoa, but this time carried by an annoying bug. The bug bites you at night, defecates at the same time and your morning scratching places the feces into the bite and thus into your blood. This charming worm feeds on your heart tissue, taking perhaps 20 years to kill you. Until quite recently half of all Bolivians had Chagas. Have a good time with this one.

Current drug treatments for this disease are generally unsatisfactory, with the available drugs being highly toxic and often ineffective, particularly in the chronic stage of the disease.

Histoplasmosis is a fungus that grows in your lungs. The spores love to inhabit bat droppings. If you venture into jungle caves or ancient Mayan tombs you can get this. When I had it my coughing would leave a trail of airborne spores that slowly floated away, like the spores of dandelions.

Enough of disease. What about critters? Glad you asked.

Everyone asks me about snakes. I have seen precisely four—that’s one snake every six years. Wear long pants and snake protectors and watch where you place your hands while scrambling about. If you venture out into the wilds of Venezuela, Brazil or Peru you might be in Anaconda country. If so then do not sleep in the open. Keep a good, long hunting knife always—always—at your side. If you are unlucky enough to be bitten by a Coral snake, you will stay where you are. Tough break.

…coral snakes are highly venomous, being the only relative of the cobra found in the New World. Despite their relatively small size, their venom is a powerful neurotoxin, quite capable of killing an adult human…Any bite from a coral snake should be considered life threatening and immediate treatment should be sought.

Jungle cats are a real danger. They will stalk you, sometimes for days. Well did Blake write

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

They are reluctant to attack a man who wears a full pack as he appears too big to be prey. When resting with pack off or while setting camp you had best be careful. Your large knife is at your side, right?

Wild pigs travel in packs, sometimes numbering 1000 animals in Brazil and Paraguay. They kill men. They usually follow river banks. Listen for their characteristic ‘clicking’ of the teeth when they are near. Trust me, they will not like you. When numbering 50 or fewer they usually take off through the forest at the sight of man. But in greater numbers they stand their ground and grind their teeth—a set of formidable weaponry. Using your machete—you did bring it, yes?—stick the lead peccary hard—and I mean hard—in the snout. No time for animal rights imbecilities now. And stand your ground! To flee might mean your death. Slowly back into a tree. If there is no tree to be had, hope for the best and hope the pigs do not surround you.

Once in Costa Rica I happened upon a jungle camp—what was left of it—of some prospectors who had had a nighttime visit by a herd of wild pigs. There was not much to see: a scrap of bone, a ruined pot, some material from clothing. Just bad luck.

Monkeys are the filthiest animals of the planet, more so even than San Francisco sodomites, though they share similar habits and diseases. Wormy, smelly, fecal and full of vermin, all monkeys should be killed on the spot. A good slingshot works just fine. Trust me.

Be aware of crocodiles. They inhabit many jungle rivers and lakes, especially in Central America and Brazil. Some of these nightmares grow to 18 feet long. When going for water at a place where they might be hiding, carry your knife. Forget swimming or bathing. If you have to cross a river, good luck. Better, try to find a village where natives will boat you across. Pray that those natives be friendly sorts.

Whenever a jungle river empties into the ocean you have two difficulties. One is crossing the thing—which must be done at low tide. This is because sharks have the annoying habit of swimming into jungle rivers at high tide. If you are stuck, relax and rest for you will have a six hour wait until you can safely cross. If you are out of water because you planned poorly—or perhaps you are simply a fool—you cannot drink the river water as it will be saline. Now, how did I learn this?

And what of the multi-legged creatures? They are a pain but seldom fatal. Spider bites hurt like anything, as do scorpion stings. If the scorpion is the size of your hand and it gets you, you will become very ill indeed. Once in Costa Rica a large, yellow scorpion fell from a roof, struck my hat—you will always have your hat on, yes?—and hit the ground. A bunch of little scorpions then slid off mama’s back and ran thither and yon.

Forget the scary stories of ‘killer bees’. You will probably not encounter them. But step gingerly in any case. They can make a nest in the ground, and if you step there you will have the time of your life. Run like Hell and keep running, for they will be after you for sure. Some biology student happened upon a bunch of these bees in Costa Rica some years back. His corpse had hundreds and hundreds of stings. It looked like a black and blue version of Rosie O’Donnell’s body after a night spent in an all-you-can-eat buffet. And keep away from wasps, whose sting is like a lighted cigarette on your skin.

Ants are a nuisance but not deadly unless they are on the march. Pick up a copy of Charlton Heston’s movie The Naked Jungle to see what they can do. Once I had the bad luck to be trapped by an army of them. I set my hammock and watched. Every jungle critter from the biggest to the smallest ran ahead of the ants—and for good reason.

Still want to venture out into the jungle for weeks with your pack and tent? Then you are an idiot. We both are, probably. Anyway, became acquainted with all of the dangers, take a course in emergency first aid, get in good shape and get decent gear.

One thing the jungle is blissfully free of is annoying environmentalists. You know, the kind who always prattle on and on about the glories of the ‘rain forest.’ I have never—but never—seen these soft gutted and addled weaklings during my many years of jungle travel.

Good thing for me. Bad thing for them if I ever bump into one.

A slingshot should work just fine.

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.—Hamlet

By now all have read of a previously unknown tribe located near the region of Brazil and Peru. Let us not be surprised that such a thing is unique. It is not. It bedevils the modern mind to imagine that there are places on the earth where such things as ‘civilization’ and ‘progress’ have no meaning—none at all.

But first things first.

Much of the area between Peru and the Brazilian state of Acre knows little of such niceties as roads and electricity. It is a tough and inhospitable place. Almost all is Amazonian jungle. Acre borders the Ucayali Region of Peru, which, while not quite as savage as Acre still is a rough go. There is only one true border crossing, and that is far to the south near Bolivia.

Even during the dry season—such as it is—travel through this region is slow, difficult and at times impossible. Most of the region simply cannot be crossed, and most of it has never felt the trod of a boot. It is only known from aerial photos and satellite maps.

Such a thing, that there remain areas of our world unexplored, is hard for most to understand. We like to believe that with our machines we can go where we please, even to the moon and to Mars. Think again. We do not know what is out there. The last towns in eastern Peru in the Ucayali Region have dirt roads that lead to nowhere and simply disappear down into the vastness of the jungle. The Inca built roads as far as they could into the jungle, but even they could not go much further than their last redoubt of Vilcabamba. For the Inca as for us, the jungle represented the border between civilization and darkness.

So when you read the lament of some travel writer who complains that ‘there is no real adventure anymore’ he simply has not done his homework. For those Indiana Jones types so inclined you might organize an expedition into the region. Keep in mind that it has swallowed up many a man. I wish you many good lucks.

Naturally, the finding of a new tribe—we call such tribes ‘uncontacted’—leads environmentalist sorts into flights of ridiculous fancy. Here is one such idiot.

He described the threats to such tribes and their land as “a monumental crime against the natural world” and “further testimony to the complete irrationality with which we, the ‘civilised’ ones, treat the world”.

If this fool thinks the tribe is part of the natural world, and that the civilization in which he lives is ‘irrational,’ then he can certainly remove himself from it and go join that tribe—or simply go off into the ‘rain forest’ to live. Of course, he will do no such thing. He sings the praises of human and natural savagery but would in no way put his money where his gaping mouth is. He will remain in the healthy, wealthy and air conditioned ‘irrational’ civilization.

Facts can be unpleasant things. But sooner or later they must be faced. Let us face them now.

The members of that tribe live in a violent state of nature scarcely above that of animals. They represent an almost complete devolution, an absolute regress, from the beginnings of civilization as presented to us by the Sumerians 6000 years ago. Their degraded existence is one no man would choose, not even the most addled and deluded Greenpeace type. They live out their abbreviated lives among the bat, the serpent, the scorpion, the puma, the crocodile, the spider, the hornet and the mosquito. Their bodies are home to a host of worms and diseases. For all we are concerned that tribe may as well be composed of aliens from another planet.

Rousseau, that great and misanthropic liar, was wrong. It is not civilization that enchains man, but nature red in tooth and claw. View the photos of the tribe and draw your own conclusions. Here is one such.

Read it and tell me again about the gentleness of natural man and of nature. Tell me again that such a life is one you would live. Tell me again that such a life is to be praised and admired. Tell me again that such a folk have much to teach our civilization. Tell me again that you would have your children live such a life.

Hobbes was right. Life in a state of nature is ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.’ If you believe that such a life is worth living then go and try to live it.

I have spent many a year in the wilds of Latin America, backpacking alone for days or weeks through jungles and Andes. Sometimes I would consult guidebooks for some basic information about the area I wanted to see. Such books are a bit scarce on the really difficult walks in Latin America. But backpacking books covering the US number in the hundreds at least. Since my return from Latin America I have read a few of them and perused many more.

Every single one of them is infected with environmental nonsense. This is understandable, since they cater to REI habitués who are themselves infected. After a while one gets used to such things and ignores them, paying attention only to the information about backpacking.

I read such books because I would one day like to know the wilds of my own nation. The problems one runs into while backpacking in Latin America are at times entirely different from those encountered here in America. Animals are a case in point. In Latin America one has to be aware of pigs and cats, both of which could kill you and devour you. North of the Rio Grande there are cats and there are bears. Backpacking books deal with bears as you would expect, from the standpoints of Greenpeace, the Sierra Club and such folks.

One may follow such advice as one chooses.

I have in my hand one such book, Hiking in the Rocky Mountains. The book states the obvious, that there are bears out there, bears both black and grizzly. If such an animal really wanted to kill and eat you, it would kill and eat you. The book has some advice on how to avoid this unpleasantness. Some of it is reasonable. Some of it is silly. Some of it might get you killed. All of it gives an insight into the mind of your run-of-the-mill environmentalist.

If one encounters a bear, the advice is:

Do not run.

True. A bear can run 32 miles an hour. This means that if you see one 100 feet away and he comes at you, you have all of 3 seconds to do—something.

Back away slowly, talking soothingly to the bear while avoiding direct eye contact.

‘Soothingly’? How does one talk ‘soothingly’ to a bear? And is taking your eyes of an animal that might want to devour you a good idea?

Do not resist or fight back.

In other words, lay down, relax and enjoy it.

Remain as quiet and motionless as possible, even if you are clawed or bitten.

Please do not disturb the bear’s dinner. That might really make him angry.

In most cases the attacking creature will eventually leave the scene once it is certain you present no danger.

In most cases?

I am sure that you get the idea. You are to respond to a bear attack by giving the bear whatever he demands of you, up to and including your life.

As befitting such a mentality, this advice is the same whether one is dealing with a bear or a mugger or an enemy nation. This sort of fellow is in all cases horrified by the use of force.

Oddly, Hiking in the Rocky Mountains concludes its advice on bear encounters with a recommendation to read Bear Attacks. I have that book in front of me, and on pages 241 – 246 is a discussion of firearms. There is the typical attempt to dissuade you from the use of guns, but most of this section goes in-depth concerning which gun is most useful to stop a bear. The author’s conclusion: a .44 Magnum round of at least 240 grain load will stop a bear. Every time. Without fail. All you have to do is hit the creature.

One can venture into bear country with or without a gun. One’s survival out there depends upon experience, training and luck. But always keep in mind that the rangers who patrol our national parks—you know, those places Like Yellowstone where no mere citizen is allowed to carry a firearm—carry guns.

Why?

And just to give you an idea of what that backpacking book wants you to lay down for, here is fine example.

If you ever see such in the wild, and you are armed with nothing more than advice from environmentalists, it will be the last thing you see on this earth.

I hate boats. I hate talking about them. I hate hearing about them. I hate reading about them. I hate it when other people talk about them. I hate them only a little bit less than I hate monkeys. I agree with Dr. Johnson.

Being on a boat is like being in prison, with a chance of drowning.

I am very glad that you asked why I hate boats.

It was the end of 1986. Tim and I were having beers in Antigua, Guatemala. Tim was the perfect traveling companion. He never complained, he hated the same things I hated and he liked beer. We were leaving the very next day for Honduras, there to venture to the Mosquito Coast. We had heard that somewhere in its impenetrable jungles there lay a lost city, the Lost White City of the Mayas. We were going to find it.

Some days later we were in Trujillo, Honduras. Like all Caribbean towns it smelled of sweat, fish and urine. To describe it as ‘dilapidated’ would be to do the place a great service. To get to the Mosquito Coast we had to find transport, and that meant a boat. We went to the port—really just a rundown dock—and talked with some captains. The village of Platano was our destination and we looked for a boat that was going that way.

Platano was at the mouth of the Rio Platano. From there you could canoe to its headwaters near the Rio Paulaya. And where those two rivers met was that lost city. Or so we thought. Naturally there were rumors of gold, so we planned to steal as much as we could, get it back to Trujillo and then on to New Orleans. All by boat. The exact details were left for later, a good thing.

We found a boat that was going to Platano. It left some hours later at night, which meant that Tim and I could head for the nearest tavern and down a few beers. More than a few.

That was a terrifically bad idea though we did not know it then. Taking our malaria medication was also a bad idea. It did not mix well with alcohol.

We staggered to the dock at the agreed upon time and got on the boat. It was a ramshackle affair, the one on the left in the photo.

Incongruously, it was transporting a freezer to Platano. That place was a tiny Indian village on the coast. It had no running water, no electricity and no ice. I did not bother to ask why a freezer was going there. Latin America is like that. Sometimes you just don’t ask questions.

Tim and I were in an excellent frame of mind. The adventure of the thing, the beer, the jungle and the open sea had their effect upon our imaginations. The boat left the dock as we sat in the back and took in the entire experience. The captain told us that it was a 6 hour journey to Platano. We were in no hurry. In the distance upon the Caribbean horizon we could see flashes of light. These were lightning bolts striking the open sea.

An hour out of Trujillo and I was not feeling the best. I am what could accurately be described as a landlubber. The ups and downs of the small boat as it made its way across the water made me more than a little queasy. It became impossible to focus my eyes on anything, yet closing them did not help my queasiness. The inevitable happened. I went to the side of the boat and vomited. A lot. More than once. My stomach emptied of beer and malaria tablets, but the vomiting did not stop.

The sea began to churn as those lightning flashes drew near the boat. There was constant thunder and waves begin to spill over the side. The captain pulled me away from the side of the boat, fearing I might fall in the sea. I had to sit in the back of the boat next to Tim, who seemed to be having a grand old time. I kept retching, and as I could not vomit over the side I had to vomit right where I was. More sea water spilled into the boat as a tropical storm hit us in full force. The boat was tossed all about, the captain having lost control. A flash of bright light, a tremendous explosion, and the boat was hit by lightning. All power was gone. We were at the mercy of wind and wave.

I had a powerful urge to urinate but could in no way make it to the side of the boat. So I simply peed where I was. The boat was now filling with water as it was tossed here and there by the sea. My urine joined my vomit and the salt water and splashed around Tim and me. This made Tim rather upset, but there was not a thing I could do about it.

My seasickness increased to such an extent that I had never felt worse in my life from any ailment. The boat was by now spinning in the open ocean like a cork tossed upon a wave. The captain was screaming at his dark instruments, trying to get power back into them. And I? I wanted it all to end. I did not care how. Death seemed just a minor thing but a great release from the situation I was in. My head lolled back and forth as I saw in my mind the boat sinking beneath the waves. I hoped that it would.

I lost consciousness for a time; I have no idea how long. I awoke to the sun peaking from the horizon. Tim was asleep. That guy could sleep through anything. I was slick wth vomit and sea water, and I stank like piss. The sea was as calm as glass. The water in the boat was gone. The captain was still messing with his equipment. I was still sick as I could be and began to vomit again.

There appeared on the water a bunch of local men in canoes. They had seen our plight and had rowed out to the boat. They came from the very village where Tim and I were headed, Platano. The caption managed to get part of an engine up and running, and we followed the Indian men to their village. The boat anchored at the mouth of the Rio Platano.

A local helped me into his canoe and ferried me to shore. I could not get out of the little boat, and so he carried me to land. Standing up was impossible. All was spinning and churning. I had to go on all fours, like a barnyard animal. A crowd of Mosquito Indians had by now gathered around. None laughed, for which I am thankful to this day. The chief of Platano—Danny by name—took me to his hut and allowed both Tim and me to stay there. I slept like a dead man.

I awakened after some hours and was delighted that I could walk again. I headed for the river, got cleaned up, and found that the village was in an extraordinary beautiful part of the Honduran jungle. Some local girls brought us rice and beans, and we devoured them—the rice and beans I mean. There was even bottled beer. It was warm, though.

Tim and I never found that lost city. In the days ahead we did manage to almost get into another shipwreck—I hate boats —made an interesting arrangement with the Honduran Army, saw a monkey get electrocuted---I hate monkeys---hitched a ride on a Nicaraguan plane loaded with illegal arms for the contras and spent more than a few hours pulling worms out of our toes.

A week later Tim’s money had run out. He boarded a bus in the capital of Tegucigalpa and traveled to Guatemala. I headed out the next day to Nicaragua, and then on to the jungles of Darien. Some months later I was holed up in Lima, Peru, living on oatmeal and bananas and trying to arrange transport to the civil war wracked regions of that nation.

For I was younger then, and sometimes very foolish.